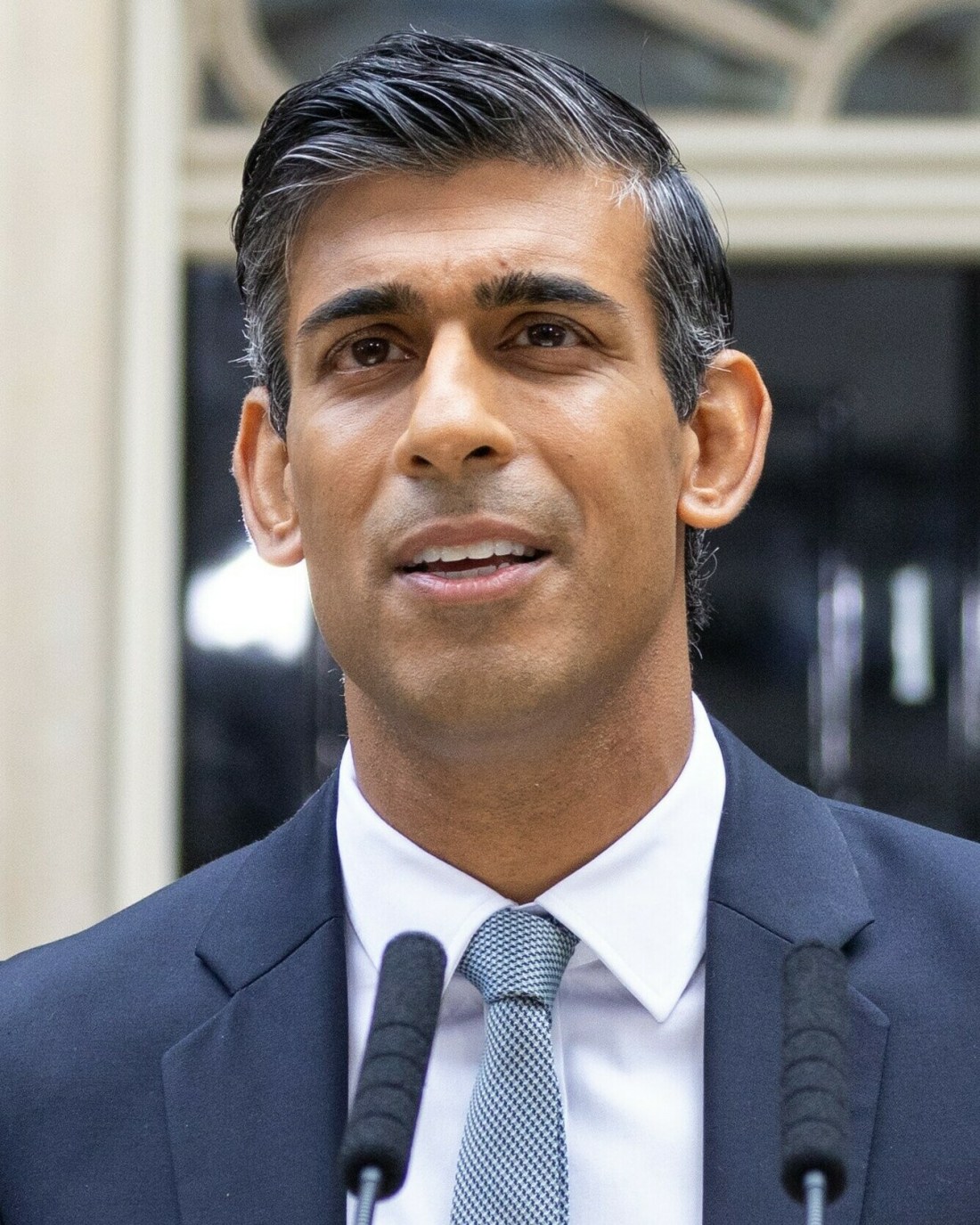

Labour in the UK currently has a double-digit lead in polls ahead of the Conservatives. The Polls immediately after the Truss/Kwarteng mini budget gave Labour their biggest lead ever, with a lead of 33% over the Tories. This has since fallen back to a 20% lead, still making Labour the strong favourites were an election to be called today. For this reason, there will be no election in the next year if the Conservatives have anything to do with it. The next election must be held at the latest in January 2025, and in all likelihood will be sometime in mid-2024. Given how terribly the Government has performed, it is hard to see how they could make it back even if the economy begins to recover.

However, just as one should never underestimate the UK Conservative Party as an electoral force, one also should never underestimate the UK Labour Party’s ability to clutch defeat from the jaws of history. It is just under two years ago that Labour under the current leadership of Keir Starmer lost the Hartlepool byelection, a so-called red-wall seat previously held by Labour since 1964. Much has happened since then but given how quickly things change in the current political climate, who knows what will be happening in 2024.

After the last UK election, I wrote a series of posts assessing why the UK Labour Party Lost. Shortly after this, a leaked report showed that factionalism was so bad within Labour that members of the Party head office tried to sabotage the 2017 election for the party as their favoured faction was not in charge. At the time few could see Labour making it back to power in 2024, with many predicting that Boris Johnson would be Prime Minister for the coming decade.

Writing those posts got me some interesting feedback. My post critical of the role of the ‘Blairite faction’ resulted in various Labour members associated with Progress and Labour First contacting me to say that I was obviously an insane Corbynista and dangerous. Later that day I posted another post critical of the role Momentum had played in the 2019 election, to which various supporters of the Corbyn loyal faction accused me of being a Blairite and a dangerous right winger. Whilst it was water off a ducks back to me, it showed how deeply divided and unwilling to engage all factions were at that time.

Starmer was elected Leader of the party in April 2020 having run on a platform of trying to bring the factions together. Specifically, Starmer’s campaign would continue the popular policies from Labour’s 2017 manifesto would be the ‘basis of the Party’s ‘foundational document’ for policy under his leadership. This recognised the fact that whilst Corbyn and the Momentum faction supporting him had become quite unpopular, the social democratic platform Labour ran on in 2017 was popular, more so than the party in itself. Now, in 2022, Starmer has said this document is being put to one side and instead the party will be “starting from scratch” leaving many to ask, what will Labour’s next policy manifesto look like?

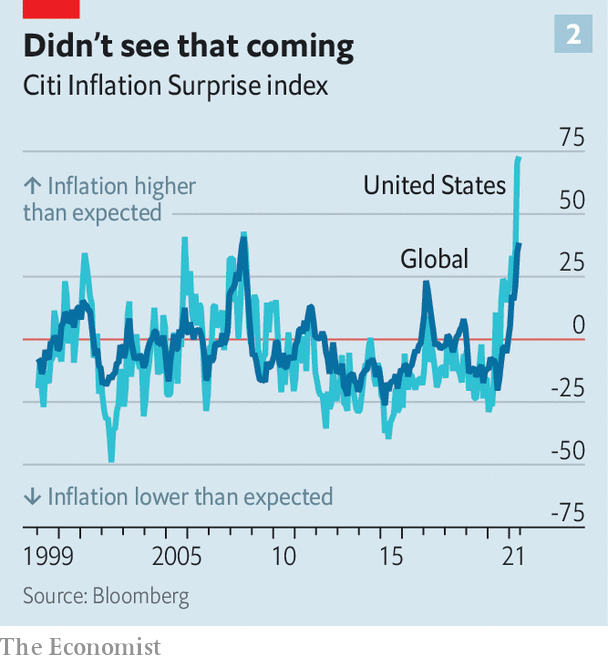

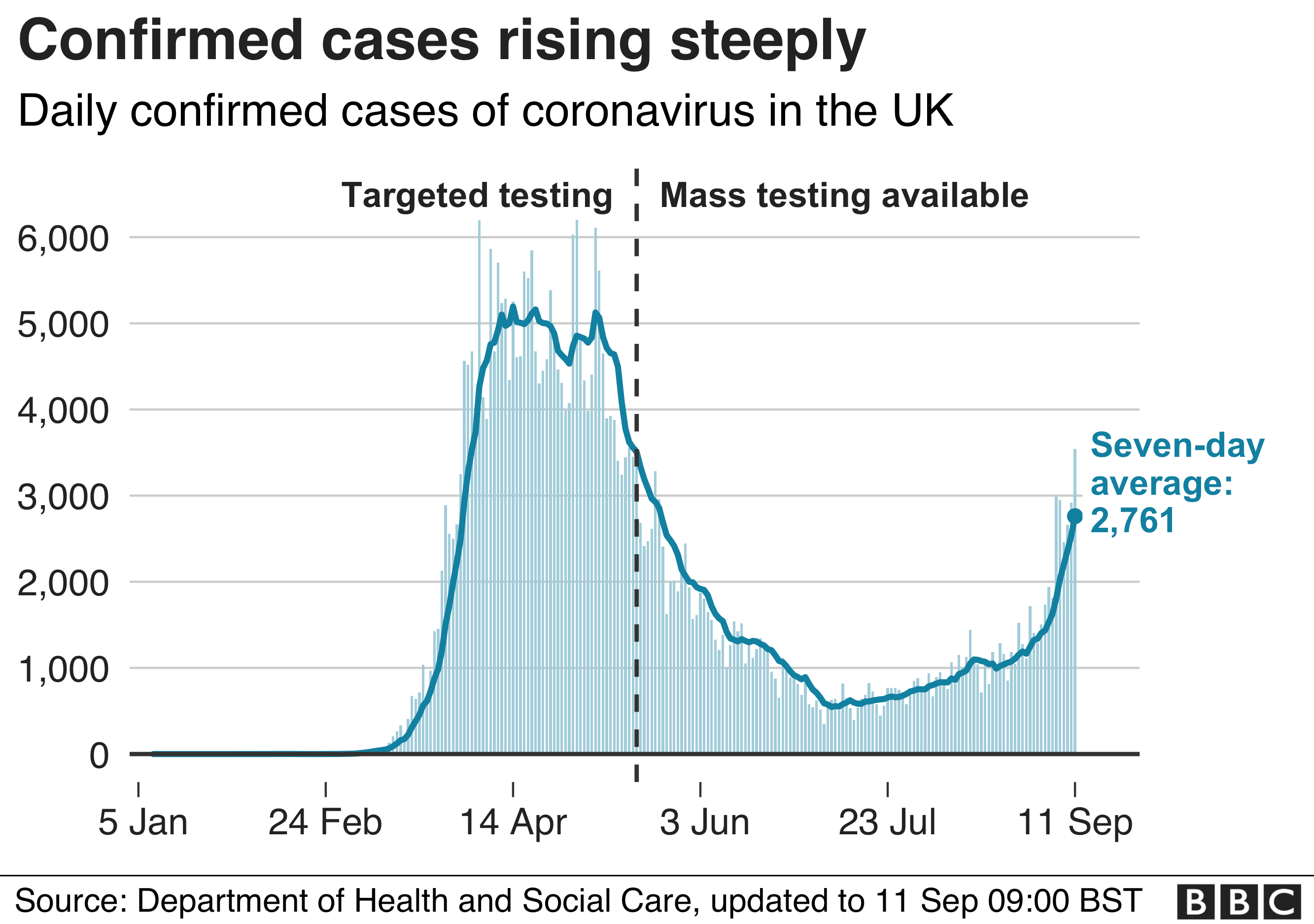

The backdrop of course is the coronavirus pandemic and the economic chaos it has caused, followed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Added to this is the economic ineptitude of the Truss and Kwateng mini-budget has meant the UK find itself in a very difficult economic situation. The challenge for Labour now, is that it needs to be seen both as credible economic managers who can repair the damage caused by the current government, yet also present a programme that addresses growing inequalities. In particular, it needs to address the fact that most people under 40 in the UK are now significantly worse off financially than their parents were at that age. The younger voters who supported Labour in the 2017 ‘youthquake’, who were disproportionately disadvantaged after the last decade of austerity, are looking to the opposition to address the growing inequalities and to create a new social contract that works “for the many, not the few.”

It is not clear how the current Labour leadership will address this, with the prevailing thinking in the party now being that people on the left have nowhere else to go, and the priority for Labour now being to win former Tory voters over. The risk is that younger voters and voters on the left become disillusioned and stay at home, or cast a protest vote for The Greens or some other candidate. This may not seem a problem now, but if polls begin to narrow by 2024, stay-home or protest-left votes in a First Past the Post electoral system could be fatal in marginal constituencies.

The current Labour leadership wish to put as much daylight as possible between the Party now and the Corbyn years. This has meant distancing themselves from some of the more popular parts of the 2017 manifesto, including public ownership of rail, energy companies and other public services, despite most party members and the British Public favouring nationalisation in this area. Starmer and shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves have said such policies do not stack up against the Party’s fiscal rules. This could create tension for a future Labour Government. Internally, the Government would be fighting both the ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ left on these issues. Also, many voters, not only those who vote Labour, would become frustrated if the private companies continue to profit from a rail system that’s expensive and unreliable or an energy market that forces people into poverty.

At the same time, those on the left of Labour need to accept a few hard facts. The 2019 election defeat was a devastating loss caused in no small part by missteps, poor tactics and wrong policy calls by Corbyn, his advisors and Momentum. Also, Labour may have increased its vote considerably in 2017, but despite losing seats, the Tories also increased their overall percentage of the vote and got more votes than Labour.

Jeremy Corbyn’s suspension from the party has seen hundreds of members, including many branch chairs, have their membership also suspended for allowing motions of solidarity with Corbyn to be moved. Corbyn’s comments in response to the antisemitism report were ill-advised, but so too has been this clumsy night of the long knives against his supporters in the party. The party has suspended members or excluded them from MP selecton for sharing articles from proscribed organisations, mostly socialist. In the case of one Milton Keynes Councillor Lauren Townsend, she was blocked from standing as an MP for liking a tweet about Sturgeon testing negative for Covid-19, hardly an act of supporting a political rival. Labour also expelled filmmaker Ken Loach, maker of ‘I, Daniel Blake’, again for associating with proscribed organisations rather than actually belonging to them.

Corbyn has done himself absolutely no favours with his frankly idiotic position on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, calling on the west to stop arming Ukraine and aligning with the Stop the War coalition’s position which appears more critical of NATO than Russia. This has now made it very easy for Starmer’s team to say that Corbyn will not have the whip restored. The left has now spent two years wasting energy trying to defend Corbyn and campaigning for him to get the whip restored. This absolutely plays into the hands of their opponents who now have good reason to expel leftists for not showing solidarity with Ukrainians.

Compare this to the US Democrats where Jo Biden’s former rival Bernie Sanders is now chair of the Senate Budget Committee, and a clear pact was made between the left and the moderate factions of the party to help beat Trump in 2020. Electoral politics is about building coalitions. The left in the UK needs to accept they alone do not have majority support and need to work with what they term the “soft left” and more centrist factions to win. The current Labour leadership need to ensure that the left still has a stake in Labour winning, and give enough to motivate the left to vote and campaign for Labour. In 2020 the Democrats learnt the hard lessons from 2016 when Sanders supporters were shunned by Hillary, resulting in many not supporting her campaign after the primaries and ultimately allowing Trump to win. In 2020, the Biden campaign made sure the left had a stake in a Democrat victory, and it paid off.

The fact is that to win elections, especially in a First Past the Post electoral system, a party needs to build a coalition of support. In 1997, UK Labour was able to build a coalition which in addition to the people who’d supported it throughout the Thatcher years, voters who’d supported the Thatcher project and its broad economic programme, but by the mid-1990s wanted something new, more socially liberal and slightly more moderate economically. This coalition held for three elections, but in 2010 many from this group of voters had drifted to the Lib Dems under Nick Clegg or back to the Conservatives under David Cameron who promised a more socially liberal and compassionate conservative party.

Starmer and the faction around want to build back the same coalition of voters they had in 1997. The problem is 25 years later, which included a decade of austerity, the voter demographics are more polarised and complex. The Conservative Party in 2022 has been forced to abandon Thatcher economics that Truss and Kwarteng tried to resurrect from the dead, and instead are now raising taxes, including for top income earners. The so-called centre-ground in politics is not the same as that in 1997. In fact, the term ‘centre’ is lazy political shorthand as if voters are easily categorised into ‘left’, ‘right’ and ‘centrists’ the latter swinging between the two and acting as king-maker. It has always been more complex than this, with people being more socially conservative on certain issues or economically liberal on others. The Brexit debate cut right across the old political divides with people across the spectrum, across class devices and cultural backgrounds being completely divided on the issue. A working-class voter in Hartlepool was not considered a swing voter until very recently, nor was an upper-middle-class voter in Kensington. Yet in the 2020s these voters will be part of the much larger ‘swing vote’ that will decide the next government.

Then there are the four nations of the United Kingdom. The majority of UK voters live in England, so inevitably this is where elections are won and lost. Historically, Labour has performed well in Scotland and Wales, with Northern Ireland having its own difficult history and different parties. Labour still performs well in Wales, having controlled the Welsh Senate since its creation in 1999. The 2021 deal between Welsh Labour and the Welsh nationalist party Plaid Cymru has been clever in securing broad support of support within the devolved government there.

The situation in Scotland is nowhere near as rosy. Traditionally, Scotland was a Labour stronghold, yet in the 2019 election, the party won only one seat up there. The Scottish National Party (SNP) have controlled the Scottish Parliament since 2007. There was a small amount of comfort for Labour in the 2022 local council elections where Labour came second to the SNP, but still a long way behind. Even the polls showing Labour with a 33% lead over the Tories nationally, had Labour was far behind the SNP in Scotland. Whilst support for independence hovers around the 50% mark in Scotland, it is consistently higher now than during the last independence referendum in 2014. The SNP have been clever to build a coalition of former Labour left voters and Scottish nationalists including some from the centre-right. By contrast, the various deals being done by Labour with the Conservatives and Lib Dems to stop the SNP risk doing more long-term harm to Labour’s chances in left-leaning Scotland.

For Labour, the strategy to win not only the next election but to start winning more often in the UK is to win over more English voters, as over 80% of the population live there. English voters have traditionally been small ‘c’ Conservative and large the ‘C’ Conservative Party usually do well, especially in the South outside of London. A wholesale return to Corbyn’s era politics is unlikely to shift this. In the short term, Labour with more of a 1997 flavour may win the next election, but it is not 1997, and very soon voters will grow restless.

English voters might be conservative but may see the need for economic reform so more people have opportunities. They will expect serious government interventions in housing, employment, education and transport. Already we have seen a Tory Government partially renationalise the railways, increase taxes to fund social care and lift Univeral Credit (the UK’s universal benefit), things the Tories would not have considered in the 1990s. The fact is society has changed. And in politics. you need to adapt. Traditionally the Conservative Party are much better at this than Labour. Whilst the Tories will probably now lose the next election, but, the size of their loss and Labour’s win will determine how long they spend in opposition. For Labour, winning more often will require nuisance and being adaptable. Yes, learn the important lessons from 1997, but know that times are now different and so too are policies and tactics. The left may not be strong enough to win, but they are still too big a block now to ignore and are more significant than in the 1990s. Like the Biden campaign, Starmer’s team will need to give the left something that means they can at least give grudging support. In turn, the left need to accept that a few important gains are better than none at all and the great cannot continue to be the enemy of the good or even the ok-ish.

The next election could well go to Labour, or at least be lost by the Tories due to their ineptness at running the country in the last few years. Labour’s internal problems have not gone away, it is just that the Conservative Party’s internal issues are now a lot worse and unusually for them have been aired in public. The opportunity for Labour is to build a winning coalition that helps them win not just the next election, but to start winning more than they lose.