Originally posted on The Standard

Trust in politicians is at a record low. This is true for the UK during its General Election Campaign, with multiple surveys showing that most voters are dissatisfied with how the UK is governed. In Aotearoa, this depressing trend is also reported in polls. What is causing this trend? Much of this is due to hubris and poor decisions by politicians. In part, however, outdated thinking and a failure to understand public opinion by the political establishment have caused this situation. Ironically, the tactics used to overcome this problem 30 years ago, are today perpetuating it.

30 years ago, we had Dot Matrix printers, Windows 95 and brick cell phones. Today we live in a world of AI, Tik Tok and 5G. While technology changes have been embraced, including in political campaigns, strategies and methods to connect with voters seem stuck in the MS-DOSS era.

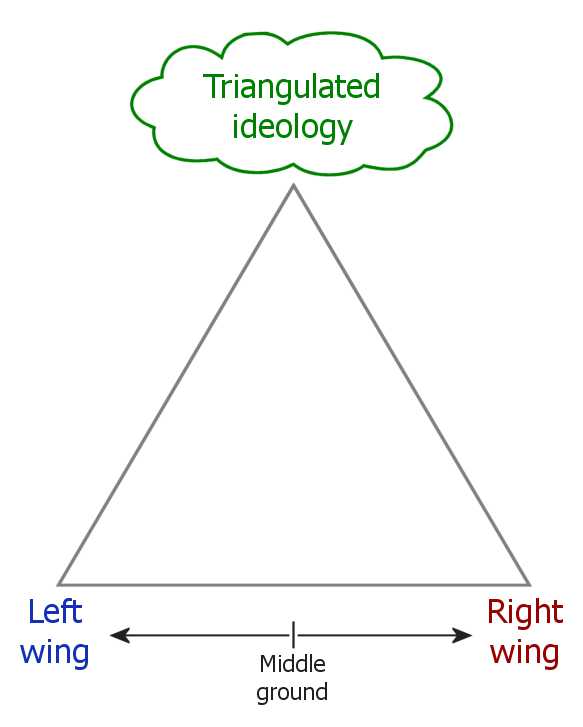

Triangulation is a political strategy whereby a politician presents a position as being above or between the left and right sides (or “wings”) of a democratic political spectrum. In the 1990s Clinton used this tactic to successfully win “centrists” who had supported Reagan in the 1980s, as did Tony Blair’s New Labour Government. The economic reforms of Thatcher and Reagan were left in place, but with a more socially liberal agenda and more resources for health and education, though often in partnership with the private sector.

Whether it was right or wrong, it is entirely understandable in 1997 that Tony Blair’s new Labour had no appetite for increasing taxes, especially after losing the 1992 election after the Tories painted Labour as the high tax party. Or if we go further back, in the 1979 winter of discontent, where the streets were strewn with rubbish because of striking binmen, was the death knell for the Callaghan Labour Government. So again, rightly or wrongly, New Labour was cautious about giving too much power to the union movement.

Smarter minds have clocked that much has changed since 1997. Whereas in the 1990s free market reforms still enjoyed reasonable support, after the 2008 financial crisis, followed by years of government austerity policies, this is no longer the case. It was the equivalent of Y2K, except it actually did cause chaos.

Following the pandemic, advocating small government, low taxation and bestowing the virtues of the market is now met with derision by all but the most hardened libertarians.

Sections of the UK media have grasped that society has changed, as have the more credible think tanks and forward-thinking academics. Many political strategists have missed the memo. Or they just have no idea how to adapt to modern politics. They continue to pitch to “the centre”, or at least to where “the centre” was 30 years ago.

Labour’s New Deal for Working People, billed as a “plan to make work pay, ensure security at work and provide the work-life balance everyone deserves”. The policy specifics are broadly similar to those introduced in the first term of Jacinda Ardern’s Labour-led Government in 2017; raising the minimum wage, banning zero-hours contracts, improving sick pay provisions and requiring employers to issue contracts which reflect actual hours worked with compensation for cancelled shifts. In a country where most people are poorer than they were at the last election, policies that lift people’s incomes are popular.

Days before the General Election was called, Conservative Home commentator Chris Hopkins argued that workers’ rights would be the wrong dividing line for the Conservatives to challenge Labour on. Chris argued that where previously the Conservatives could argue for flexibility and a lightly regulated workforce on the grounds that it would boost economic growth, now voters have “wised up” and that the “old political rules no longer apply”. He goes on to say:

Where the public may once have conceded workers’ rights for a perceived higher standard of living via growth and jobs, they have lost trust in the Conservatives as effective stewards of the UK economy.

Think of it like this. If your main job is now more precarious, your mortgage has significantly increased and you are working a second gig to make up for it, I’d imagine stopping ‘fire and rehire’ and having the ‘ability to switch off’ would look like a pretty good offer. And it would look good to Conservative supporters as much as anyone else.

Have the Conservative Party taken heed of this sound analysis? Conservative Business Secretary and future Tory leadership hopeful Kemi Badenoch has claimed “Labour’s new employment regulations are going to make it very hard to hire, strangling employment”. Despite 14 years of weak employment protections failing to stimulate the economy, Badenoch and her colleagues in government still think this is a strong dividing line with Labour.

She is not alone in this. Lord Peter Mandelson, Business Secretary in the Blair/Brown New Labour Government warned in March that Labour’s employment law changes must not be rushed or go further than “the settlement bequeathed by New Labour”. Mandleson was one of the architects of New Labour and has advised the current Labour leadership on strategy and policy. While the ‘Black Prince’ is undoubtedly a smart cookie, his fingers are not on the pulse of public opinion on this issue.

Sharon Graham, the General Secretary of Unite, the largest Labour Party-affiliated trade union in the UK has warned that Labour has watered down proposals to ban fire and rehire, and sectorial bargaining plans have been delayed. It is no surprise that the Unite leader wants to push Labour further, but in this case, what is being asked is quite modest. A union representing over 1.2 million workers in the UK, which is growing each year, should not be dismissed out of hand.

Another example of triangulation leading to poor policy positions is tax. The Conservative Party have made a key pitch of the 2024 campaign that Labour will increase taxes and they will cut them. Labour has in fact ruled out increasing income tax, VAT or national insurance, which are the main taxes which bring in government revenue.

Taxes have risen since 2019 despite the Conservatives promising to cut them in their previous manifesto. The tax burden has risen to 36% of national income, the highest it has been since 1949. This has been due to a freeze on the income tax threshold, increases to corporation tax and a windfall tax on energy companies.

While Tory party faithful decry their party breaking their 2019 promise, the economic reality is that the government cannot cut taxes without harsh cuts to public services. The election of Liz Truss as Tory leader was largely a response to this, and the harsh reality of unfunded tax cuts destroyed the Conservative Party’s reputation as sound economic managers. The voting public is more interested in public services that work than tax cuts which fuel inflation and do little to help people.

The British public would much rather the government invest in crumbling public services like the NHS, and polls have consistently shown this for some time. The public can see roads full of potholes, schools falling down, the NHS overwhelmed and there not being enough police on the streets.

The recent debate on how quickly each party would increase military spending in the next term was another example. The public knows that whatever is promised now, if the situation in Ukraine, Gaza or elsewhere in the world deteriorates further, the government will have no choice but to increase military spending. In this context, it is no wonder that the Conservative Party’s promise to cut taxes, without a proper explanation of how it will be paid for, has fallen flat.

Labour has ruled out tax increases and is banking on economic growth to help them fund public services, as it did during the Blair/Brown Government. While measures like planning reform and improving the trade deal with Europe will help, there is no guarantee that economic growth will happen fast enough to fix Britain’s woes in the next parliamentary term. The Shadow Chancellor’s commitment to having the fastest-growing economy in the G7 is ambitious, to say the least.

In New Zealand, the decision of the Labour Government in 2023 to rule out a ‘wealth tax’ saw the party’s polling decline, albeit from an already poor position. It confirmed voters fear that Labour had no serious plan to fix public services in a third term if re-elected. By contrast, the UK has had 14 years of Conservative Government and the public is crying out for change. Once in Government, a future Labour Government will face the same challenges if they rule out new forms of revenue, especially if aspirations of economic growth fail to materialise.

The UK Institute for Fiscal Studies has said there is a ‘conspiracy of silence’ on how public services will be funded if there are to be no tax rises in the next five years. My Dad has a theory that given the choice of conspiracy or cock-up, it is almost always a cock-up. The cock up here is parties making political calculations on old models, based on public attitudes 30 years ago.

Society is a much more complex place in 2024. We carry smartphones with 10 times more memory than 1990s PCs, which give us access to vast amounts of information online. We also are much more connected and events which once took hours or days to be reported are now on our phone newsfeeds in seconds.

People’s political views and voting intentions are vastly different now from what they were in the 1990s. The size of political swings in democratic nations has increased substantially in recent years. The so-called political centre was always lazy shorthand to describe a section of the voting public who broadly speaking decided elections. Society, much like technology, is much more complex than it was in the 1990s. The politicians who are first to adapt to this change will be the ones who ultimately succeed.