Welcome to my 200th blog post, the first since the 2024 UK General Election.

In what came as a shock to absolutely no one, the Conservatives lost. Badly.

Today the corridors of Westminster felt like the first day of school. 334 new MPs have come in to get their passes working, set up their email and find a desk. A couple of freshers nervously asked if they were allowed on the red carpet/ the House of Lords end (they are). Many were walking around steering in awe at the statues and artwork and excitedly looking around the Commons.

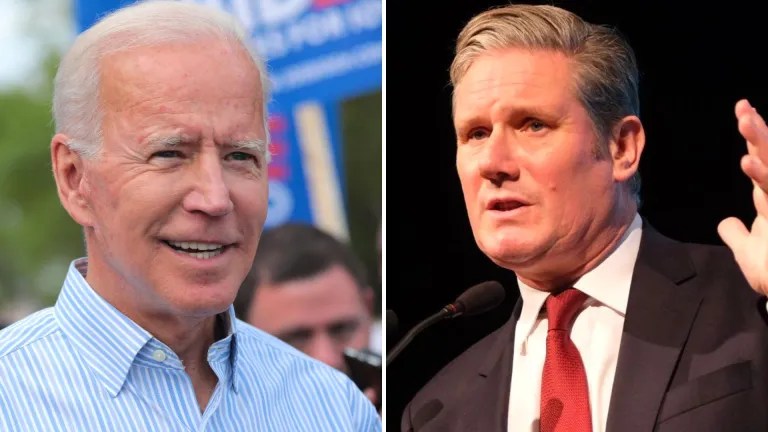

The election result was a massive swing against the Tories. 121 MPs will be the lowest number of Conservative MPs elected in the party’s history. Labour is by far the largest party and will govern with a majority of 172. Below are the full results showing the results for all MPs and parties elected:

| Party | Seats | Seats (change) | Total Votes | Share of the Vote |

| Labour | 412 | +211 | 9,704,655 | 33.7% |

| Conservatives | 121 | -251 | 6,827,311 | 23.7% |

| Liberal Democrats | 72 | +64 | 3,519,199 | 12.2% |

| SNP | 9 | -39 | 724,758 | 2.5% |

| Sinn Fein | 7 | 0 | 210,891 | 0.7% |

| Independent | 6 | +6 | 564,243 | 2.0% |

| Reform UK | 5 | +5 | 4,117,221 | 14.3% |

| Green | 4 | +3 | 1,943,265 | 6.7% |

| Plaid Cymru | 4 | +2 | 194,811 | 0.7% |

| DUP | 5 | -3 | 172,058 | 0.6% |

| SDLP | 2 | 0 | 86,861 | 0.3% |

| Alliance Party | 1 | 0 | 117,191 | 0.4% |

| UUP | 1 | +1 | 94,779 | 0.3% |

| TUV | 1 | +1 | 48,685 | 0.2% |

In 2019, Labour received 10,269,051 votes and won just 202 seats. In 2024, Labour received 9,704,655 votes but won 412 seats. In 2017, Labour won 12,877,918 or 40% of the vote, compared with 33.7% of the vote in 2024.

I will come back to the elephant in the room, the lack of proportionality in the First Past the post-electoral system.

The feedback on the doorstep is reflected in the numbers above. Many voters were undecided leading up to the election and unenthusiastic about either main party. When pressed, it became clear many former Conservative voters would not be supporting that party again. 2024 was the election that the Tories lost, and badly.

On the surface, 33.7% may not seem like a strong result for Labour, in terms of overall support. We need to consider some of the following factors:

- Tactical voting played a significant role in this election. Many would-be Labour voters living in places like Devon voted Liberal Democrat to stop the Tories. Curiously, the Liberal Democrats went from 3,696,419 votes, equating to 11.6% in 2019, whereas on Thursday their total votes went down to 3,519,199, but due to lower turnout, this equates to 12.2% of the vote. The Lib Dems now have 71 MPs, instead of the 8 they got in 2019.

- The voter coalition built by Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour in the 2017 election of younger progressive voters, has now moved to the Greens. On Thursday the Greens received 1,943,265 votes equating to 6.7% of votes cast. In 2019, the Greens received 865,715 votes or 1.1% of the vote.

- In New Zealand or other countries with more proportional voting systems, it is common to look at the centre-left and centre-right bloc rather than just what the parties received. Labour and the Greens together received 40.4% of the vote compared with the Conservatives and Reform who received 38%. The Liberal Democrats were largely targeting Tory seats this election. They stood on a broadly social democratic platform and made it clear that unlike 2010 they would not support a Conservative Government after the election. So adding their 12.2% to the Centre-left bloc we get to 52.6%.

- So while First Past the Post has produced a result that is not proportional, and in my view is an appalling voting system, a different voting system like the one used in Germany and New Zealand would have still resulted in a Labour Government (though almost certainly in coalition) and a crushing defeat for the Tories.

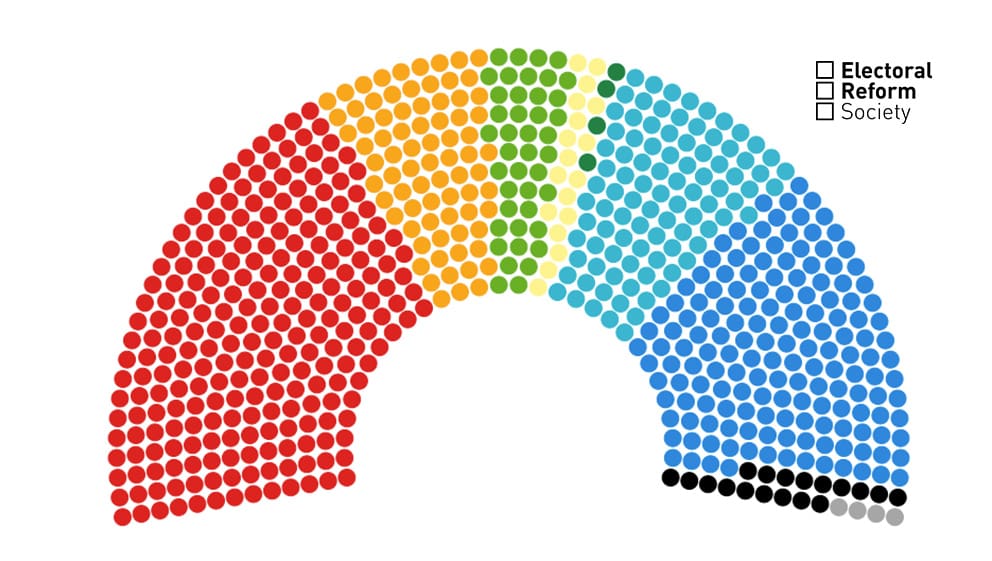

The UK Electoral Reform Society have put together modle showing what the result would have looked like using the Additional Member System used in Scotland and Wales:

The problem with this is that if there were a different voting system, people would likely not vote the same way.

The broader problem with the proportional representation debate in the UK is they tend to advocate only specific alternative voting systems like AMS or AV. This election result will rightly see more people call for proportional representation. Just as New Zealand did before changing voting systems in 1993, UK voters need the opportunity to explore all viable alternatives to First Past the Post.

Those who blame the rise in Reform for the Tory Party’s misfortune need to look at the bigger picture. In 2015 UKIP, Farage’s old party, received 3.8 million votes compared with Reform’s 4.1 million last week. While Farage’s new political vehicle certainly cost the Tories votes in key marginals, there is evidence of former Labour voters also switching to Reform.

The Conservative Party lost because their vote went from 13,966,454 votes or 43.6% in 2019 to 6,827,311 or 23.7% in 2024. The number of people who voted Tory halved in just five years. Why? Their response to the pandemic, party-gate, the Liz Truss mini-budget and their failure to manage the small boats crisis in the channel. They were terrible at managing the economy allowed public services to decline.

In terms of the two major party’s vote share, in 2019 the Labour and the Conservatives together received 75.% of the vote, and in 2017 82.3%. Last week the two combined received 57.4% of the vote.

One feature in this election is the 6 independent candidates, many of whom ran on the issue of Gaza. In one case it caused former Labour front-bencher Jonathan Ashworth to lose his Leicester South seat. Other senior Labour MPs such as Wes Streeting or Jess Phillips saw their majorities reduced drastically as many Muslim voters abandoned Labour for Independent candidates, or refused to vote. Starmer’s Labour Party was initially reluctant to call for a ceasefire in Gaza. Had there not been a significant swing against the Conservatives, Labour losing support from large sections of the British Muslim community could have been very damaging.

Former Labour Leader Jeremy Corbyn was also elected as an Independent MP in Islington North. Again, his position on Gaza was a factor in Corbyn’s success.

In Scotland, support for the embattled Scottish Nationalist Party (SNP) collapsed. Labour now has 37 of Scotland’s 57 seats, compared with one seat in 2019. It would be a mistake to view this as a collapse in support for Scottish Independence as a cause. A Norstat/Sunday Star Times poll published just a fortnight ago found that 47% of Scots still support independence, while 47% support staying in the union. Other recent polls on Scottish independence have also been quite close. The election result, rather than spelling the end for Scottish Independence, instead may result in the SNP being the main political vehicle for this cause.

In Northern Ireland, Sein Fein won the most seats. This is consistent with the most recent Stormont and local government elections in Northern Ireland. The decline of the Democratic Unionist Party post-Brexit has in part fuelled division on the Unionist side with two other rival parties challenging them.

Wales no longer has any Conservative MPs. Labour has controlled the Welsh Senedd since it was created in 1999. Despite the recent scandal surrounding Vaughan Gething the new Welsh First Minister, Labour continue to dominate politics in that nation.

This was a change election. Not only is there a new Government, but politics will be different. After this election, there are 264 women MPs, a record in Westminster. The Cabinet will also have more women than any before it. There will also be more MPs from ethnic minority backgrounds, though there is some concern that this diversity is not fully reflected in the cabinet.

Britain has been in decline in recent years. It will be difficult for the incoming government as they inherit a poor economy, crumbling public services and a country whose standing internationally has diminished considerably since Brexit. It is no wonder voters lacked enthusiasm during this election.

For Labour, the next five years will be an opportunity to show the country they can be trusted with power. Things will be tough and any honeymoon could be short-lived. That said, voters will take time to forget, let alone forgive the mess left by the previous Conservative administration. While people may not yet be enthusiastic about Labour, they can could no longer stomach the Tories.